Louis Paulsen

A Chess Biography with 719 Games

Hans Renette

448 pages | hardback | 108 illustrations | $75.00

Jefferson: McFarland, 2019

Jonathan Hinton

Author Hans Renette has established himself as a leading chess historian with the publication of his immense 2016 biography of Bird1 and two years later (in collaboration with Zavatarelli) the fascinating study of three leading Berlin players Neumann, Hirschfeld and Suhle.2 Both books were beautifully produced by McFarland & Co, famous for its series of historical chess titles. Renette has again teamed up with McFarland to provide us with his latest work – a deeply researched biography of Louis Paulsen (1833–1891). Surely a winning formula?

One thing is clear from the very beginning of this book – Renette has once again demonstrated his brilliance as a historian and researcher. The level of enquiry and information gathering that has gone into this work is highly impressive and can only be the result of much detailed, lengthy and diligent research. For this the author is to be heartily congratulated. As we shall see, there are shortcomings but the culprit is not the author.

Paulsen’s name is known in the chess world for two main reasons. First, most of us will recall his being at the receiving end of a famous mating combination by Paul Morphy. Second, he made a significant contribution to opening theory – in particular the Paulsen Variation of the Sicilian Defence which has withstood the scrutiny of nearly a century-and-a-half of human and more recently computer-assisted analysis. But of course, his life and career were so much more than that, and Renette presents the full story.

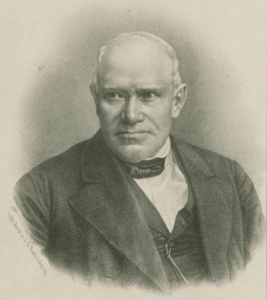

Frontispiece portrait

Louis Paulsen was born in 1833 at the family’s woodland and farmland estate, Nassengrund in Germany. He had two brothers and two sisters who reached adulthood, and all were taught chess by their busy father who would play a single game against them each Sunday. His brother Wilfried was a talented player who went on to became a well-known expert. Louis was evidently fascinated by chess and would go through his games in his head while in bed.3 This undoubtedly was one of the factors that enabled him to become so proficient at blindfold chess.

His other brother, Ernst, emigrated to the United States in 1849, and in his absence Louis and Wilfried became actively involved in running the family estate. They played chess locally and by all accounts defeated everyone they met. On the death of their mother in 1853, Ernst travelled home and Louis accompanied him on his return to the US the following year. The brothers eventually settled in Dubuque, Iowa where Ernst established a wholesale tobacco business; Louis was his bookkeeper and in his spare time played chess against the local community where he continued to defeat all-comers. He also began to play simultaneous blindfold exhibitions which drew much acclaim from the press. The standard of play was not hugely impressive, as this brevity shows.

Paulsen – Wullweber

Blindfold exhibition, Dubuque USA, 1856

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 f5?! 4 Bc4 fxe4?

4…exd4, 4…Nc6 or 4…Nf6 are less painful.

5 Nxe5! dxe5 6 Qh5+ Kd7 7 Qf5+ Kc6 8 Qxe5 a6 9 d5+ Kb6 10 Be3+ c5 11 dxc6+ Kxc6 12 Qxe4+

It turns out that 12 Nc3 is the easiest win.

12…Kc7

13 Nc3?

This should probably still win although it throws away a large part of White’s advantage. 13 Bxg8! Rxg8 14 Nc3 Nc6 15 Bf4+ Bd6 16 0–0–0 wins.

13…Nc6?

After 13…Nf6! the attack on the queen gives Black a tempo which offers him some chances of survival.

14 Nd5+?!

Simply 14 Bf4+ Kb6 15 Rd1 wins the queen.

14…Kb8 15 Bb6

15…Qg5?

15…Nf6! 16 Qf4+ Bd6 17 Bxd8 Bxf4 18 Bxf6 Re8+ 19 Be2 Bh6 20 Bc3 Bf5 recovers one pawn and Black survives into the endgame, albeit one with only slim chances of a draw.

16 f4 Qh4+ 17 g3 Nf6

Too late.

18 Bc7+ Ka7 19 Qe3+ b6 20 Qxb6 mate

This is typical of the games Paulsen played at this time. He was clearly talented, as his ability to play blindfold demonstrated, but a lack of serious competition hampered his development. Nonetheless, his fame in the United States chess world was growing, and his talent such that by 1857 he was invited to the famous tournament held in New York that year, The First American Chess Congress. He was not the favourite, of course, since this was the event that Morphy dominated, defeating Paulsen in the final (+4 -1 =2) as we all know. Paulsen’s second prize sealed his reputation and there was demand for his blindfold exhibitions, notwithstanding Morphy’s opinion of them. In a private letter to Daniel Fiske, editor of The Chess Monthly, Morphy wrote:

‘By the way, and entre nous, I have seen no blindfold game of Paulsen’s that justifies the somewhat ridiculous praises that are bestowed upon him, and while I admit that he may be able to play more games at one time than I can, I claim that an impartial comparison between the specimens of blindfold play we have both given to the public will lead every true chess man to the conclusion that Paulsen is not the American blindfold player.’4

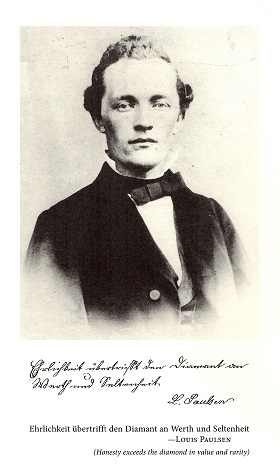

Paulsen as a young man

(Cleveland Public Library, John G. White Collection)

In character Paulsen was thoughtful, quiet and diffident. On the chessboard this manifested itself as careful, correct and sometimes rather defensive play; he was also a painfully slow player, a trait for which he became notorious. Morphy had become understandably infuriated by this: for example, the second game of their final had lasted an astonishing fifteen hours. Fiske wrote that ‘after the German had taken repeatedly thirty, forty-five and fifty minutes (and in some instances over one hour) upon his moves, Morphy became so thoroughly worn out that in his haste he made what should have been his second move first and was only able to draw a won game.’5

Paulsen remained in the United States, primarily in Chicago and Dubuque, where he enhanced his reputation with blindfold displays. He also began a diligent study of chess, particularly the openings, which he had identified as a key area for self-improvement. He wanted to become a stronger player since he had ambitions to challenge Morphy to a match, although to his great disappointment these came to nothing. Then, in 1860, Louis returned to the family estate in Germany as its accountant. He continued to study the openings and gave numerous blindfold exhibitions.

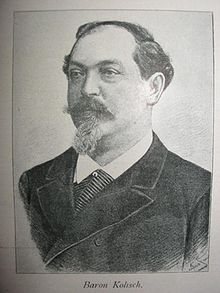

Ignaz Kolisch

In 1861 he travelled to the British Chess Association’s annual tournament in Bristol. Without any time limit imposed on the players, Paulsen’s slow play disrupted the tournament schedule. It was particularly painful when in the first round he met another slow player, Ignaz Kolisch. Their second game had to be adjourned after nine hours with only 22 moves having been played. In the end, Paulsen – armed with his immense theoretical knowledge – defeated Kolisch and went on to win the tournament. The decisive game against Kolisch shows how much he had improved:

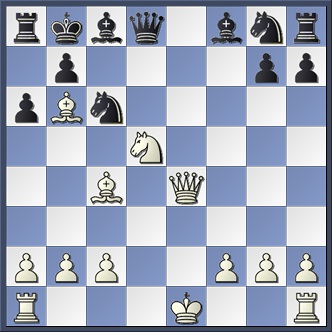

Kolisch – Paulsen

British Chess Association Tournament, Bristol 1861

Evans Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Ba5 6 d4 exd4 7 0–0 d6 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 d5 Na5 10 Bb2 Ne7 11 Bd3 0–0 12 Nc3 Ng6 13 Ne2 c5

Although 13…Bg4 might be stronger Paulsen has studied this line of the Evans Gambit and knows that a vigorous counter-attack along the c-file is usually an effective remedy.

14 Qd2 f6 15 Kh1 Bd7 16 Rac1 a6 17 Ne1 Bb5 18 f4

18…c4! 19 Bb1 c3! 20 Rxc3

The c-pawn could not be taken by the knight or queen since the rook and knight respectively hang. And 20 Bxc3 allows 20…Nc4! and 21…Ne3 winning the exchange.

20…Nc4 21 Qc1 Rc8 22 Bd3?

Renette points out that 22 a4! offers some counter-chances after 22…Ne3 (or 22…Nxb2 23 axb5 Rxc3 24 Nxc3 Nc4 and things are level) 23 axb5 Nxf1 24 Nf3 Rxc3 25 Bxc3 Ne3 26 Nfd4.

22…Be3! 23 Qc2 Nd2 24 Rg1

24…Rxc3?!

A little inaccurate. There was nothing wrong with 24…Bxg1 25 Nxg1 Rxc3 26 Bxc3 (or 26 Qxc3 Bxd3 27 Qxd3 Qa5) 26…Nc4.

25 Qxc3?

Better, per Renette, is 25 Bxc3! Bxg1 26 Kxg1 Nc4 27 a4! Ne3 28 Qd2 Bxd3 29 Qxd3 Ng4 30 h3 Nh6 and White has some compensation given the passivity of the black knights.

25…Qb6! 26 Bc1

The neat tactic is that 26 Bxb5? Nxe4! threatens the queen and mate on f2.

26…Bxg1 27 Nxg1 Bxd3 28 Nxd3?

Or 28 Qxd3 Nb1! 29 Qc2 Qa5! and Black escapes with the material.

28…Nxe4 0–1

After Bristol, Paulsen based himself in London where he met Kolisch in a protracted match lasting nearly two months. There were several ‘grandmaster draws’, which attracted some criticism, and the match was abandoned as a tie before either party could reach the required nine victories. Paulsen was one game ahead at the termination (+7 -6 =18). He then visited Manchester before returning to London to finish as second prize winner in the great tournament of 1862, won by Adolf Anderssen ahead of inter alia Owen, MacDonnell, Steinitz and Blackburne. Later that year Paulsen showed what a powerful match player he was when he tied his first contest with Anderssen (+3 -3 =2).

Paulsen – Anderssen

Match game 4, London, 1862

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 e6 3 g3 d6 4 Bg2 Bd7 5 Nge2 Be7 6 0–0 Nc6 7 d4 cxd4 8 Nxd4 Nxd4 9 Qxd4 h5?!

The type of attacking move with which Anderssen used to crush weaker players. It is highly enterprising but premature and against a good defence is likely to lead only to a weakened position.

10 h3

Perhaps Anderssen was seduced by setting the rather obvious trap 10 Qxg7?? Bf6 11 Bg5 Bxg7 12 Bxd8 Rxd8 and Black is a piece ahead.

10…Bc6 11 Rd1 e5

Again very committal.

12 Qd3 Qd7 13 b4 b6 14 a4 Rc8 15 a5 b5 16 a6!

Assessing that any weakness on a6 is out-weighed by the pressure on b5 and Black’s lack of development.

16…g6?!

Further time-wasting.

17 Bf1 Nf6 18 f3 0–0 19 Be3 Rb8 20 Ra5!

Looks like a master versus amateur game. Black’s position is desperate.

20…d5

If here 20…Bd8 then 21 Qxd6! and the tactics favour White.

21 Nxd5 Nxd5 22 exd5 Bxb4 23 Ra2!

Calmly consolidating.

23…Ba8 24 Rb2 Bd6 25 Rxb5 Rxb5 26 Qxb5 Qf5 27 Qe2

True to his style, avoiding unnecessary risks.

27…e4 28 fxe4 Qxe4 29 Bxa7 Qa4 30 Bf2 Rc8 31 Qb5 Qxc2 32 Re1 Bf8 33 a7 Qf5 34 Bg2 Rc2 35 Rf1 Kh7 36 Qb8?!

Renette suggests that 36 Qb6! is more accurate since the c5 square is then unavailable for Black’s bishop.

36…Bc5!

The only attempt to confuse matters.

37 Qf4

Löwenthal, in The Era, says that 37 Bxc5 would have given Black the chance to draw the game by 37…Rxg2+ and 38…Qxd5+. But of course, 37 Bxc5?? is a losing blunder since the line given immediately leads to mate rather than a draw.

37…Qd7 38 Bxc5

Giving up his queen in return for rook and bishop. The white passed pawns should prove decisive.

38…Rxg2+ 39 Kxg2 Qxd5+ 40 Qf3

40…Qd2+

Renette gives 40…Qa2+ 41 Kg1 Bxf3 42 Rxf3 f5 as a better try, since White has to find 43 Rf4! with the plan of R-b4-b8 while keeping f5 under attack.

41 Kg1 Bxf3 42 Rxf3 1–0

In contrast to the line in the previous note, Black has no way of defending f7 and a8, since 42…Qa2 (or 42…Qd5) loses immediately to 43 Rxf7+.

From 1862, Paulsen lived and worked in Germany and (with the exception of two international tournaments in Vienna) played the rest of his chess career there. Between 1862 and 1866 he gave a variety of blindfold exhibitions at German congresses, as well as informal games and matches against the leading German players. Take this brief encounter from Leipzig 1863.

von Schmidt – Paulsen

Leipzig, 1863

Ruy Lopez

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 d4 exd4 5 e5 Ne4 6 0–0 Be7 7 Nxd4 0–0 8 Nf5 d5 9 Nxe7+ Nxe7 10 f3?! Nc5 11 Be3 Ne6 12 f4 Nf5 13 Bd2 c6 14 Bd3 Qb6+ 15 Kh1 Nc5

White’s hesitant play has gifted Paulsen a lovely position.

16 g4?

White lashes out but in doing so severely weakens his own defences.

16…Nxd3 17 cxd3 Ne3! 18 Bxe3 Qxe3 19 Nc3 f6 20 exf6 Rxf6 21 f5 h5!

Obvious but effective.

22 Re1?

Black still dominates after 22 Rg1 but White at least gets some play along the g-file.

22…Qg5 23 Re8+ Kh7

24 Qb3

White has a tactical try here in 24 Ne4!? dxe4 25 Qb3, eyeing g8. It should however prove insufficient after 25…Bxf5! 26 Qg8+ Kh6 27 gxf5 Rxe8 28 Qxe8 Qxf5.

24…Qxg4 25 Rg1 Qf3+ 26 Rg2 Bxf5! 27 Ree2 Bh3 28 Ne4

Black announced mate in three with 28…Qf1+ 29 Rg1 Qxg1+ 30 Kxg1 Rf1 mate. 0–1

Paulsen’s chess activity continued in this vein, with offhand and blindfold chess interspersed with match victories in 1864 against Max Lange (+5 -2) and Gustav Neumann (+5 -3 =3). Then, during the winter of 1865-66, he was struck down with jaundice. The illness at one point seemed to be serious enough to be life-threatening, and it appears to have affected him for a significant period thereafter, perhaps (Renette suggests) even causing him to curtail the frequency and scale of his blindfold displays. This, and the Austro-Prussian conflict of that time, led to a period of relative inactivity on the chess scene. Moreover, around this time Paulsen seemed very reluctant to play in any tournament where he might have to face his brother Wilfried. Things changed somewhat from 1869 onwards when the death of their father provided Louis with the freedom to pursue his chess career with renewed vigour. At Hamburg 1869 he tied first with Anderssen (losing a play-off) but then, at the famous Baden-Baden tournament of 1870, he faltered against Anderssen and Steinitz and had to settle for fifth place. Although he did well at Krefeld 1871 he again suffered a relative failure in the major tournament at Vienna 1873 (he tied for fifth).

Adolf Anderssen

For the next few years German chess was in the doldrums and it was not until 1876 that Paulsen’s tournament schedule resumed at the Central German Chess Association’s second congress in Leipzig. A surprise loss to Göring meant he finished half a point behind the three winners, Anderssen, Göring and Pitschel. Nevertheless, a prize was put forward by the latter two players to be awarded to the winner of an Anderssen–Paulsen match. Paulsen again showed his resilience in match play by besting his venerable opponent +5 -4 =1, despite a 0-3 start. The match was tense and error strewn. Take this position from the sixth game, for example.

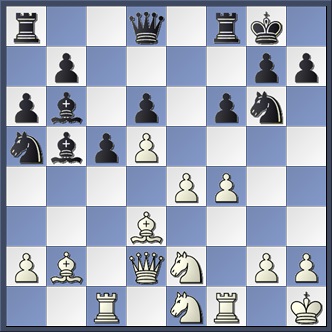

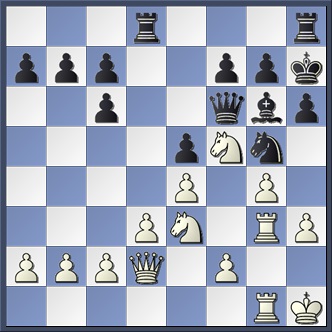

Paulsen – Anderssen

Leipzig, 1876, Game 6

Paulsen is a clear pawn ahead but starts to lose the thread.

23 Rde1?!

23 Nd3 is simpler.

23…Rdf8 24 Nxd5??

If 24 Nd3 Black has 24…Rxf1+ 25 Kxf1 Bh2+ followed by 26…Rxf1 However, Paulsen inexplicably overlooks that the idea is refuted by the obvious 24 g3, when after 24…Bxf4 25 gxf4 Nc6 26 Qe6 White retains his advantage.

24…Nxd5 25 Rxf7?

A further inaccuracy: 25 Qe4 Rxf1+ 26 Rxf1 Rd8 (or 26…Bh2+? 27 Kxh2 Rxf1 28 Bxd5+ and White’s dominant bishop gives him any winning chances) 27 Re1 Kg7 28 Bxd5 Qxd5 29 Qxd5 Rxd5 30 Re7+ leads to an imbalanced endgame where White has several pawns against the bishop.

25…Qxf7 26 Qf3 Rd8 27 Qe4 Kg7 28 Rf1 Nf6 29 Qh4 Qe7 30 Re1 Qd6 31 Re6

31…Qh2+ 32 Kf2 Bg3+??

A terrible move that throws away all the advantage. 32…Rf8 wins immediately.

33 Qxg3 Ne4+ 34 Rxe4 Rf8+ 35 Qf3 Rxf3+ 36 Kxf3

Now White has material equality and a nicely coordinated position. He eventually won the game on move 104 but only after further errors from each side. 1-0

In 1876, Göring conceived the idea of a jubilee chess celebration to honour the ‘Altmeister’ Adolf Anderssen. The idea seemed to galvanise German chess clubs who enthusiastically embraced the concept, appointing representatives to the organising committee and attracting financial support. The event took place in Leipzig and included Anderssen himself as well as leading players such as Zukertort, Winawer, Göring, Englisch, Schallopp and both Louis and Wilfried Paulsen.

This part of the book is greatly enhanced by the inclusion of detailed analysis and appraisal of Louis Paulsen’s games by Richard Forster, who wrote extensively on the subject in his ‘Late Knight’ column for the website www.chesscafe.com. Forster’s assessment of Paulsen is interesting:

‘The games examined . . . seem to justify Paulsen’s great fame as an early exponent of the “modern school”. His opening play with Black makes an especially profound impression. Both in modern and classical set-ups he showed great proficiency and imagination.’6

Although there were errors in his games, Paulsen played some excellent chess and won the tournament by half a point from Anderssen and Zukertort. This win against Göring is an impressive example of his positional style.

Paulsen – Göring

Leipzig, 1877

Four Knights

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 0–0 0–0 6 Bxc6 dxc6 7 d3 Bg4 8 h3 Bh5 9 Kh1 Qe7

Paulsen now begins his strategic encircling.

10 Rg1 Rad8

Black’s aimless play does little to prevent White’s build-up. He should have considered some piece exchanges.

11 Qe2 h6 12 Nd1 Bc5 13 g4 Bg6 14 Nh4 Kh7 15 Be3 Nd7 16 Nf5 Qe6 17 Rg3 Rh8 18 Bxc5 Nxc5 19 Nde3 Qf6 20 Rag1 Ne6 21 Qd2!

With the modern idea of playing on both flanks.

21…Ng5?

A poor move. 21…Rde8 and 21…b6 are safer alternatives. Now Paulsen pushes home his advantage with some incisive play.

22 Qa5!

Targeting the a7, c7 and in some lines the e5 pawn.

22…Ne6 23 g5! Nxg5

If 23…hxg5 then 24 Ng4 traps the queen.

24 h4 Bxf5 25 hxg5 Bxe4+ 26 dxe4 hxg5 27 Ng4 Kg8+ 28 Kg2 Qg6 29 Qxe5 f6 30 Qe6+ Kf8 31 Re1!

With the idea of 32 e5!

31…Re8

Now Paulsen finds an original tactic to finish the game.

32 Ne5! Qxe4+

Mate on d7 is threatened and if 32…Rxe6 then 33 Nxg6+ picks up the rook on h8.

33 Rxe4 Rxe6 34 Ng6+ 1–0

Immediately after Paulsen’s triumph in the tournament, he engaged Anderssen in the last of their three matches. Yet again he was victorious, this time by the score of +5 -3 =1. The games were full of interest although there was more than a sprinkling of material errors from both players. Anderssen’s age, particularly after a tough tournament, would surely have counted against him.

In 1878 Paulsen won the West German Chess Congress at Frankfurt am Main, ahead of Schwarz and Anderssen, who was playing in his last competitive event before his death the following year. At the first congress of the German Chess Association in 1879 Paulsen finished second behind Englisch, ahead of Schwarz. He wanted a match against the winner but this could not be arranged so instead he played Schwarz, winning in impressive style (+5 -2). These dominating performances led the German press to consider him a worthy challenger to Steinitz.

‘Paulsen played truly excellently in this match and we doubt whether he ever achieved a greater playing strength throughout his chess career of more than two decades. It would be very desirable and interesting for the chess world when one day a match between Paulsen and W. Steinitz could be arranged.’7

Although at this time it did appear that Paulsen could be a match for any player in the world, his results in major tournaments in the next two or three years did not quite support this view. Thus in 1880 he finished only ninth out of sixteen players at Wiesbaden (Blackburne, Englisch and Schwarz headed the field). Further disappointment followed a year later in Berlin at the second German Chess Congress – Paulsen finished equal ninth, well behind the leading contenders Blackburne and Zukertort.

‘The Sixteen Leading Chess Players of the World, 1886’ (Paulsen standing third right)

(Cleveland Public Library, John G. White Collection)

The giant tournament in Vienna 1882 was a true test of his ability. The eighteen-player double-round all-play-all event featured nearly all the leading players, including Winawer, Steinitz (who won after a play-off with Winawer), Blackburne, Mackenzie, Chigorin and Mason. Paulsen’s final place of eighth seems to be a fair reflection of his standing in the chess world. Despite a poor start he rallied towards the end of the tournament and produced some fine chess such as this smooth victory over second prize winner Winawer.

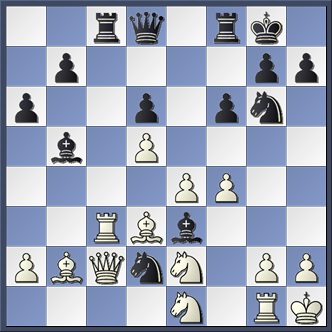

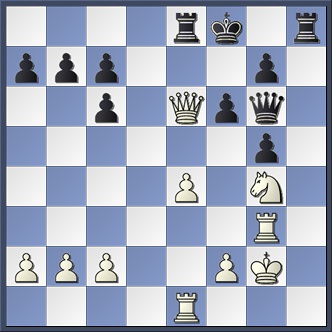

Paulsen – Winawer

Vienna, 1882

Scotch

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Qh4 5 Nb5 Bb4+ 6 c3 Bc5 7 Qe2 Bb6 8 Be3 Qd8 9 Bxb6 axb6 10 g3 d6 11 Bg2 Nge7 12 Nd2 0–0 13 Nf3 Bg4 14 h3 Bxf3 15 Bxf3 f5 16 exf5 Rxf5?

Weakening.

17 Be4 Rf6 18 0–0 Qd7 19 Bg2 Raf8 20 Rad1 Kh8 21 Kh2 Re6 22 Qd2

22…Ne5?

This is a mistake since it allows Paulsen to manoeuvre his pieces to commanding posts. Renette gives 22…Ng8 as a better idea.

23 Nd4! Rh6 24 f4! Nc4 25 Qe2 d5 26 Rfe1! Re8 27 Nf3! Nd6 28 Ne5! Qf5 29 Ng4! Rh5

Paulsen’s classy positional play has given him the opportunity to make a neat tactical breakthrough.

30 Rxd5! Qxd5

Mate on e8 prevents the knight capturing the rook, and 30…Qg6 31 Ne5 Qh6 32 Rxd6! wins.

31 Bxd5 Rxd5 32 Ne3 Ra5 33 Nc4 Ng8 34 Qxe8!

True to his nature Paulsen simplifies into a won ending.

34…Nxe8 35 Nxa5 Nd6 36 Nb3 g6 37 Nd4 h6 38 Ne6 c5 39 Rd1 Nc4 40 b3 Ne3 41 Rd3 Nf5 42 Rd7 Nf6 43 Rxb7 Ne4 44 g4 Ne3 45 Rxb6 Nxc3 46 Nxc5 Nxa2 47 Rxg6 Kh7 48 f5 Nb4 49 Ne4 Nbd5 50 Nf6+ Nxf6 51 Rxf6 Nf1+ 52 Kg1 Nd2 53 b4 Nf3+ 54 Kg2 Nd4 55 Rd6 Nc2 56 b5 Ne3+ 57 Kf3 Nc4 58 Re6 h5 59 b6 hxg4+ 60 hxg4 Na5 61 g5 Kg8 62 Re7 Kf8 63 f6 Nc6 64 Rc7 1–0

In 1883 Paulsen finished in a lowly fourteenth place in the third German Chess Congress in Nuremberg. Renette suggests that he had lost his enthusiasm for studying chess, including opening theory which in the past had provided him with many wins. This marked a period of inactivity, and he did not take part in another event until 1887 at the fifth meeting of the German Chess Congress in Frankfurt am Main. Paulsen played some decent games but lost to a number of tail-enders, finishing in a tie for eighth. At Nuremberg the following year he managed fifth out of six, but only a point behind the winner Tarrasch, before finishing his formal chess career at the sixth German Chess Association Congress in 1889. His play in this tournament, in Breslau, was a fitting end to his life in chess since he produced some excellent games and tied for fourth place. Sadly Paulsen, who had suffered from diabetes for a number of years, played no more and died in 1891 at the relatively young age of 58. Glowing tributes throughout the chess world recognised his significant contribution to the game.

So that then is the life and career of Louis Paulsen. From his early days in the United States, where he crossed swords with the great Morphy, through his years playing the European champions such as Anderssen, Steinitz, Zukertort, Blackburne, Chigorin and Tarrasch, he proved a redoubtable opponent. To his credit, he never lost a match and had some notable triumphs, such as those over Anderssen and Neumann. Examining his games reveals that generally he disdained speculative attacks and he was seen primarily as a positional player; although perhaps it is fairer to say that he strove to be a correct player, and this set him apart from his early contemporaries. This search for accuracy on the chessboard mirrored his attention to detail as an accountant and is consistent with his shy, reserved character. It is apparent too that his strength matured through study; at his peak in the 1870s he was a far better player than when he battled Morphy. His prowess at blindfold chess and contribution to opening theory are also noteworthy.

As for the author, it cannot be overstated how brilliantly Hans Renette has researched his subject. Paulsen’s family life and character are portrayed with great clarity, and the evolution of his life and chess career is laid before us. The games include annotations made by the chess writers at the time, augmented by Renette’s perceptive modern analysis, which complements and never overshadows the original comments.

And what of the flaws mentioned at the start of this review? Well, unfortunately the publisher McFarland has somewhat let the author down in the copy-editing/proof-reading stages of the production process. English is clearly not Renette’s native tongue, but the publisher should have recognised this and provided the necessary support to remove ungrammatical, ambiguous or poorly translated prose.

Regrettably it is obvious that this did not happen properly. It should not have been beyond the wit of a half-decent editor to identify the flaws in the following, which are representative of the problem:

‘Many excellent set up game would be marred during the Zeitnot phase’ (p.5)

‘Not much of excellent defense was demonstrated by Paulsen when he met Morphy’ (p.11)

‘In 1823, probably after continued studies, he got a book published’ (p.16)

‘Apparently these manuscripts went lost’ (p.19)

‘Best does White holds the center intact’ (p.80)

‘Black already stands very agreeable’ (p.141)

‘in which Paulsen maintained his idea that giving the odds of pawn and move were not worth being seen as an odd’ (p.144)

‘Paulsen played very strong until now and could constantly bow on a slightly better position’ (p.145)

‘which may explain the awkward final’ (p.162)

‘and Louis engaged in many offhand play’ (p.196)

‘Its contents was very similar to the report in the Wochenschach, but gave a few more details as well. Paulsen got a fever on first Easter Day and only two weeks later he was able to resume his daily walks’ (p.405)

Overall though, the book is so superbly researched and the chess so fascinating that the patches of clumsy translation do not really spoil the reader’s enjoyment. With games against most of the leading players from Morphy to Steinitz, and the historical perspective expounded so well, I heartily recommend it to any lover of chess history.

Notes

- Hans Renette, H.E.Bird: A Chess Biography with 1,198 Games (McFarland, 2016).

- Hans Renette and Fabrizio Zavaratelli, Neumann, Hirschfeld and Suhle: 19th Century Berlin Chess Biographies with 711 Games (McFarland, 2018).

- Der Nationale Demokrat, 17 May 1858.

- David Lawson, Paul Morphy, The Pride and Sorrow of Chess (David McKay, 1976).

- Lawson, Paul Morphy.

- Richard Forster, ‘Late Knight’ column 52, www.chesscafe.com.

- Minckwitz, Deutsche Schachzeitung (December 1879).