The Moves That Matter

A Chess Grandmaster on the Game of Life

Jonathan Rowson

352 pages | hardback | £20.00

London: Bloomsbury, 2019

Sarah Hurst

The Moves That Matter is the very personal story of Jonathan Rowson’s search for meaning in life and chess. A question that arises throughout is why chess players often seek to justify their passion with external metrics, such as alleged educational benefits. The obvious answer is that chess lacks funding and needs to prove its worth, otherwise it looks like ‘as elaborate a waste of human intelligence as you can find outside an advertising agency,’ in the words of Raymond Chandler. Financial considerations aside, chess players like Rowson would like to think the game is more than just wood pushing on a board. But the Scottish grandmaster and philosopher often takes a leap too far in his assertions and his positions turn out to be rather unsound.

The book’s chapters have titles like ‘Thinking and Feeling’, ‘Winning and Losing’, ‘Power and Love’, ‘Truth and Beauty’ and ‘Life and Death’. Rowson is a Scottish grandmaster and three-time British champion who gave up professional chess to become a philosopher. He is full of regret for not making it into the world elite and for leaving the game behind, and despite many attempts to describe how chess still enriches his life and how much he loves being a husband and father, he still sounds unfulfilled and lost. A cascade of ‘vignettes’ that range from autobiographical episodes to musings on Nelson Mandela and Whitney Houston, in no particular order, fail to convince the reader of the points Rowson is trying to make and often seem to have a tenuous connection to the chapter’s theme.

For example, in the chapter ‘Thinking and Feeling’ Rowson informs us that he is pathologically late. As with everything, he finds a deep reason for this: ‘Lateness functions like a cushion to protect the vulnerable parts of our psyche from their terror of unmediated social contact.’ He then annoys me, a typically punctual person, by saying,

‘I must confess that I am a little wary of those who are steadfastly punctual, as if they have nothing to retain them, nothing to hide or protect, nothing worthy to divert them from the false god of good timekeeping. I am more inclined to like and trust people who are a little late.’

Then, of course, there is a segue to chess and time management.

Cover of the US edition

I was more interested in Rowson’s insights into the life of a professional chess player, such as the experience of assisting Vishy Anand in preparation for his World Championship match against Vladimir Kramnik. Rowson’s discovery that his analysis engine isn’t powerful enough brings home to him the harsh reality of top-level chess in an age when the strongest human player is no match for a computer. If chess becomes a matter of who can memorise the most lines identified by a machine, it casts into doubt all the other romantic ideas about chess as a metaphor for battle or sex – as depicted graphically by Rowson in one memorable paragraph – and as a wonderful enhancement to the school curriculum, which is another thing he struggles to demonstrate.

Many of Rowson’s statements just left me baffled. ‘The Italian amateur Pozzini has a modest rating, but his hairstyle and designer glasses made him look like a blues brother, so I was not taking any chances,’ he says of a tournament encounter. Why would his opponent’s appearance have a bearing on his estimation of how dangerous he would be at the board? This isn’t explained – presumably it’s humour. We are also treated to claims such as, ‘Chess is not so much a path to happiness as a ritual where we free each other from the pressure to be happy,’ and, ‘. . . chess is about many things, but ultimately I think it’s about trying to purge what the Buddhist philosopher David Loy calls ontological guilt.’

The most intriguing section in the book for me was a puzzle involving three people on an island with blue faces who didn’t know what colour their faces were, but knew they were either blue or red, and had to kill themselves if they found out. When a visitor from Scotland tells them that at least one of their faces is blue, they all kill themselves. Even after reading Rowson’s explanation I’m still trying to work through the steps in my head. But the entertaining diversion was as random as everything else in the book. It needed tighter editing, including spotting that the name ‘Kurnosov’ was spelled ‘Kursonov’ numerous times.

The Moves That Matter is aimed at non-chess players primarily, so there is a lot of basic explanation of how chess works, but precisely for that reason it could have benefited from some diagrams to really illustrate why some positions were beautiful or exciting. Some readers might have a hard time grasping what it is that Rowson is so enthused by. Flowery adjectives, academic jargon, quotes from famous people and symbolism are no substitute for the real thing: chess itself.

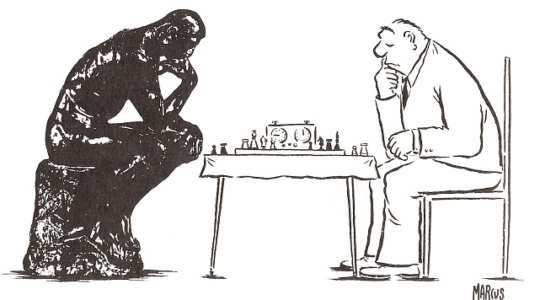

Display illustration by Fred Marcus in Schach Cartoons (Rosenheim: Rosenheimer Raritäten, 1988)

Interesting comment on punctuality .. I regard those who habitually turn up late as rude, selfish tosspots who care more about their own time than that of other people.

But, he’s the grandmaster 🙂