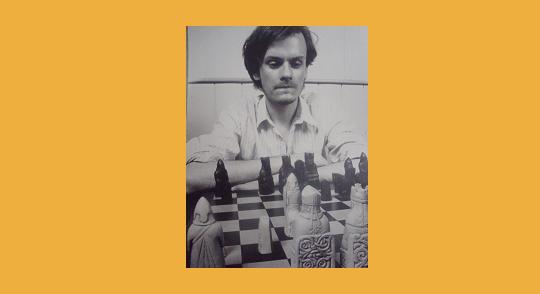

Stuart Conquest recalls his reckless youth

When one’s surname is Conquest, and when one spends ten years of one’s life in the town of Hastings, then the line: ‘Is your middle name Norman?’ (or similar witticisms) does tend to crop up with alarming frequency. I hold my parents entirely responsible, for it was their decision to move away from the rustic charms of Braunton, North Devon, and cross instead to the historically vulnerable town of Hastings, East Sussex, an area officially designated as ‘1066 Country’ by the local tourist board. In Braunton no-one had even heard of the Norman Conquest.

After I’d been up to the castle, and jumped off the pier a few times, and been blown off my bike by Force 10 gales whilst cycling along the sea-front, I started thinking that I’d exhausted all the possible leisure activities that the town had to offer, and so I informed my parents that I was completely and utterly bored with life. That’s when my father took me to the Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club for the first time.

I was nine years old. I was already keen on chess – my father had taught me the game when I was five or six – and I suppose that I had some sort of talent for it: I could beat my mother blindfolded (me, not her). But I had never been to a proper chess club before, so I imagined that I would meet other children of my own age, like at school chess club, except that was full of kids who thought that ‘pawn’ was a rude word. I wanted serious opposition.

The sun was high up in the clear, blue sky, and a refreshing summer breeze glided up from the calm sea, gently stirring the golden sand. An attractive young girl had stretched out on a beach-towel; she motioned to a tanned, muscle-flexing hunk down by the water’s edge, and he slowly walked over to her and started to rub coconut oil into her shoulders.

‘For the last time, will you turn that TV off, and get into the car,’ my father was saying.

Outside it was pouring with rain. I hit the on/off switch, and the ‘Bounty bar’ girl disappeared from the screen.

The chess club is in the centre of town, just around the corner from the railway station; it is a tall, terraced building, with huge red lettering outside that says: ‘CHESS CLUB’, and yet were you to poll Hastings residents and ask them: (i) For which game is the town most famous?, and (ii) Where can one go to play this game?, then the most popular responses would almost certainly be: (i) crazy golf, and (ii) down on the sea-front by the trampolines. Perhaps we should have formed a combined ‘Chess and Crazy Golf Association’.

I once played crazy golf in the pouring rain with two chess club colleagues, and on the last hole one of them won a free game by fluking a hole-in-one, so the three of us went around again. Life was never dull in Hastings.

On the front door it says: ‘Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club. Founded in 1882.’ There was a notice of the opening hours, and a sign which read: ‘Open every day of the year except Christmas Day.’ Next to that was a piece of paper that said: ‘Please do not leave bicycles in the hallway.’ Clive Chamberlain once had his old bike pinched from there while he was upstairs playing a match game, so the following week he came on a brand new ten-speed racer (indexed gears, cantilever brakes, Reg Harris frame) and lashed it up to the outside railings with all manner of chains and padlocks. When he came downstairs again four hours later the thing had been nicked. After that some joker put up a new sign: ‘Please do not leave bicycles tied to the railings.’

On the front door it says: ‘Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club. Founded in 1882.’ There was a notice of the opening hours, and a sign which read: ‘Open every day of the year except Christmas Day.’ Next to that was a piece of paper that said: ‘Please do not leave bicycles in the hallway.’ Clive Chamberlain once had his old bike pinched from there while he was upstairs playing a match game, so the following week he came on a brand new ten-speed racer (indexed gears, cantilever brakes, Reg Harris frame) and lashed it up to the outside railings with all manner of chains and padlocks. When he came downstairs again four hours later the thing had been nicked. After that some joker put up a new sign: ‘Please do not leave bicycles tied to the railings.’

Inside was a notice board with all kinds of information, and on a small table there was a musty old envelope addressed to some Club member whom nobody had ever heard of, and who had probably pushed his last pawn circa 1900. Along the walls were black and white photographs from past Hastings Congresses, with captions like ‘Fine plays Tartakower; Alexander looks on’, or my favourite, ‘The Russians at Dinner.’ (I often thought of swapping all the captions around to see if anyone would actually notice the difference.) Halfway up the stairs was the toilet, from the window of which you could just glimpse the trains coming into the railway station. As you reached the landing there was a door marked ‘Kitchen’ to your left; the other door said ‘Club Room’. My father pushed the door open, and in we went.

It was like crossing into the Twilight Zone, or stepping through a time-warp into a tiny universe from the last century. Octogenerians in their best Sunday suits sat hunched over long wooden tables, mesmerised by the steady ticking of the antique chess clocks, resolutely scanning the huge boards before them; every so often a head would be raised, a hesitant arm would hover and then descend, and one of the heavy Staunton pieces would reluctantly set off on a new trajectory, changing the position forever. Eyes would meet, secret thoughts would pass across the table, and the players would return to their previous poses, acting out the same roles that they had invented for themselves fifty years ago or more. The passage of time did not affect the people in this room. They were immune, preserved like exhibits in a sacred museum. They were, perhaps, immortal.

It was like crossing into the Twilight Zone, or stepping through a time-warp into a tiny universe from the last century. Octogenerians in their best Sunday suits sat hunched over long wooden tables, mesmerised by the steady ticking of the antique chess clocks, resolutely scanning the huge boards before them; every so often a head would be raised, a hesitant arm would hover and then descend, and one of the heavy Staunton pieces would reluctantly set off on a new trajectory, changing the position forever. Eyes would meet, secret thoughts would pass across the table, and the players would return to their previous poses, acting out the same roles that they had invented for themselves fifty years ago or more. The passage of time did not affect the people in this room. They were immune, preserved like exhibits in a sacred museum. They were, perhaps, immortal.

I coughed. I didn’t do it to attract attention, I did it because the room was absolutely brimming with cigarette smoke and tobacco fumes. Someone put their pipe down and went to open the window an extra two centimetres. A particularly ancient-looking gentleman sat with his back to the fire, propped up in his chair with cushions; he was the only person without an opponent, although there was a chessboard on the table in front of him, and so my father led me across to ask if he would be kind enough to give me a game or two.

‘I was fascinated by the fact that a game played fifty or a hundred years ago could be exactly reproduced on my own chess set’

I sat down in the chair opposite and my nose just peeked over the top of the massive oak table. I had White. I brought my feet up and sat on my heels: it was obviously better to be able to see my opponent’s pieces as well as my own. The old man was regarding me with a curious sort of stare, as if he and I did not come from the same planet. I grinned at him, and struggled to lift the knight from g1 to f3 without knocking all the pawns over, a task which proved so difficult that I eventually gave up and opened 1 e2-e4 instead. I looked up, half fearing a rigorous imposition of the dreaded ‘touch, move’ rule, but my venerable opponent was staring vacantly into the middle distance, his eyes glazed over, as if he had chosen precisely this moment to hypnotise himself. I waited patiently for five or ten minutes, until my father gently tugged at my sleeve, and told me that we had better be leaving now.

Later I found out that my opponent’s name was Doctor Cox, and that no-one had seen him play a single game of chess in over half a century, although he always came and took his place by the fire, and once or twice he even agreed to arbiter a kriegspiel match, although one imagines that this was because there was no other living soul in the building at the time, for Doctor Cox was not the most observant of men. Possibly his last game had been circa 1900, against the gentleman whose letter remained unopened downstairs in the hall. Possibly it was even Doctor Cox’s letter, asking the fellow what the devil he was playing at, and when was he going to pass by and finish that game that they had begun last week. Possibly, just possibly, the redoubtable Doctor Cox had never played chess in his life.

Anyway, I didn’t care too much about all that stuff. I made up a phoney score-sheet with names and the date and everything, wrote out the moves ‘1 e2-e4 Resigns’ on it, faked old Cox’s signature at the bottom, and then showed it to all those nerds at school, which meant that they had to put me on board one for the chess team. And that’s the story of how I won the first-ever game that I played at the world famous Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club.

First published in

Great story, Stuart.

When we moved to Hastings at the end of 1978, I worked in the Post Office just around the corner from the club. I used to come into the club at lunch break, one o’clock. On one occasion, Mr Cox who was the only one there asked me if I was a member. When I said no, he said ” well you have no business coming in here!