Jimmy Adams

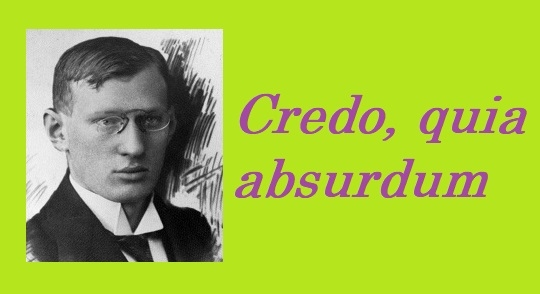

My book is a chess book so I did not want to wander too far beyond its natural boundaries, but I think Credo, quia absurdum, with which Tartakower concluded his article on Hypermodern Chess in The Tree of Chess Knowledge, could now do with some explanation.

In his letter to Chess magazine in 1959, Mr A. Eccles suggested that the phrase Credo, quia absurdum, translated into English, meant ‘I believe this, because it is impossible’, or in his opinion, ‘Truth is stranger than fiction’. Ed. Winter quotes this with no comment, even though it is not correct. If we look at a translation of the original writings of Tertullian, an early Roman preacher who first used the phrase in response to being challenged on the veracity of Christian Scriptures, we read:

‘And the Son of God died: it is by all means to be believed, because it is absurd.

And, buried, He rose again: it is certain, because impossible.’

So Credo, quia absurdum means ‘I believe it because it is absurd’. Or perhaps in modern colloquial English: ‘It must be true, they couldn’t have made it up even if they tried!’

Therefore, in the chess context, though it seems ‘absurd’ to say that the standard move 1 e4 is a loser, nobody in their right mind would make such a claim unless there was some truth in it. So you had better believe it!

But here we might just mention that the move 1 e4 does lose in ‘losing chess’ as the late Evgeny Gik demonstrated, whereas 1 e3 wins for White.

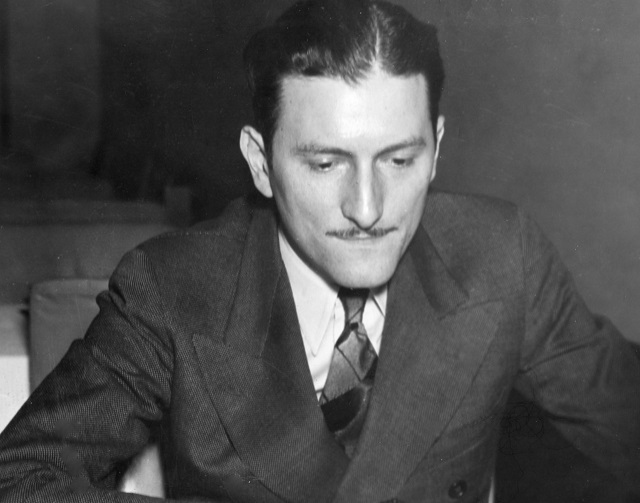

For three decades Al Horowitz was ‘Mr Chess’ of New York City. He was a strong international master, writer of books and newspaper columns and owner/editor of the ‘picture chess magazine’ Chess Review.

Anyway, as another example of a justified use of Credo, quia absurdum, I’d like to quote the following anecdote as related by Al Horowitz in the American magazine Chess Review, December 1946, under the header Rubber Check-mate (i.e. the check that bounced!).

‘Once upon a time, during one of the Hungarian Championships, Balla was playing Breyer. Both players were hunched over the board. Suddenly von Balla looked up excitedly: “Mate in two!” he crowed. The spectators all stared at Breyer. He looked rather bored, but otherwise showed no reaction. Astonished, Balla stared at the position again, and to his horror, he found that the mate in two didn’t exist!

However, after further study, he found the solution. “Mate in three!” he shouted, more excited than ever. But Breyer still looked bored. Crestfallen Balla turned back to the position, grew pale . . . there was no mate in three either!! What to do? He studied and studied and studied. Suddenly he came to a conclusion . . . the spectators hung on his words . . . “I resign” he whispered.

Check, mate.’

Well, the story is too ‘absurd’ not to have at least a grain of truth in it. Which it did! My guess is that Al Horowitz had heard a corrupted version of what really happened from a Hungarian player who had arrived on the New York chess scene.

Zoltán von Balla was the victim of mistaken identity

In any case, it appears that Breyer’s opponent was Lajos Asztalos and not von Balla, as in the following game Breyer himself reveals that his opponent announced a mate that wasn’t there!

Asztalos – Breyer

Budapest 1918

31 Qh3?

Breyer: ‘An hallucination!’

In fact White would be doing very well after 31 Rhf4 Rd7 32 R1f3 d3 33 Qh3 when all of his five pieces are in the attack and Black has to tread carefully.

31…Qc6+ 32 Rf3

If 32 Kg1 dxc3+ 33 Be3 Bxe3+ 34 Qxe3 Rf6.

32…Ng5

33 Rh7+

Breyer: ‘White announced a mate in two.’

33 Bxg5 Qxf3+ 34 Qxf3 Rxf3 is better but still does not save White.

33…Nxh7 34 Qh6+

Of course after 34 Bh6+ Kh8 35 Bxf8 Black must not release the pin on the rook by 35…Qe8?? because then 36 Qxh7+ Kxh7 37 Rh3 is mate. However, did Asztalos have another hallucination and think 34 Bh6+ Kh8 35 Rxf8+ (illegal!) Nxf8 36 Bxf8 was mate?

34…Kh8

Evidently, Asztalos thought he could now play 35 Rxf8 mate, forgetting this was against the rules. On realising this he resigned.

0–1

Incidentally, the game opened with a Vienna Gambit – thus confirming once again that after 1 e4 White’s game is in the last throes!

On his website Ed. Winter gives another slightly different version of the tale, as related by Irving Chernev, but no game.

C.N. 10555 noted that he [Jimmy Adams] began work on the Breyer book over 30 years ago.

Again, Credo, quia absurdum! But it’s true. In fact by now the time span is even approaching 40 years.

Over the years 1981–1986 I would spend occasional Saturdays at Peter Szabó’s house, talking chess and translating Breyer articles from Hungarian to English. This was an intellectual delight, and when we eventually got through the researched material, I prepared the ‘first edition’ of the book for the printer.

Peter Szabó was a gentleman and a scholar. Following the Hungarian uprising of 1956, Peter sought political asylum in Great Britain and became a prominent member of the Metropolitan Chess Club in the heart of London.

In 1986, I arranged to see Gyula Breyer’s granddaughter, Csilla Csanádi, who informed me she was coming to London. We agreed to meet at a language school she was attending over the summer and, Credo, quia absurdum, this establishment was right next door to the Park Lane Hotel in Piccadilly where the first leg of the Kasparov–Karpov world championship return match was being held!

Csilla was instrumental in bringing home the remains of her grandfather, Gyula Breyer, from Bratislava to Budapest, where he was reinterred with honour, alongside other Hungarian heroes

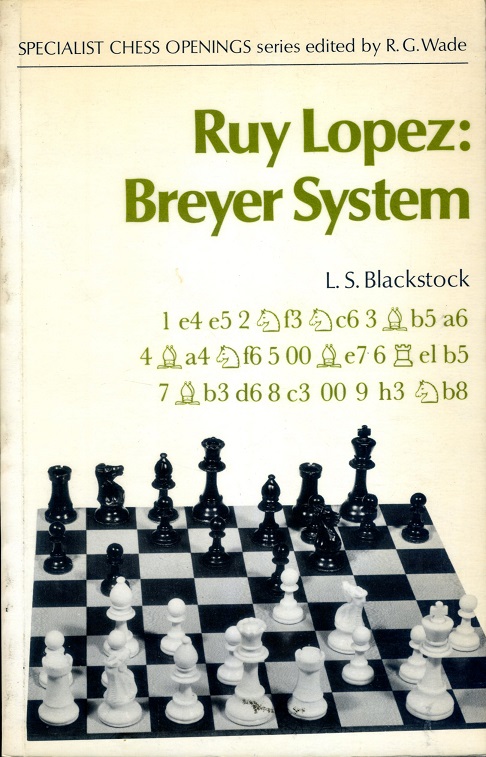

I remember going into the school and entering a room packed with students and immediately picking out Csilla, I don’t know how. Something to do with chess culture, I suppose. Anyway she gave me a ‘postcard’ with a picture of her grandfather and this is the image that appears on the cover of the book. We then went next door where B.H. Wood of Chess magazine was running a bookstall and I was happy to be able to get her a copy of a Batsford book on the Breyer Variation of the Ruy Lopez by Les Blackstock to take home as a souvenir.

Much later, when it came to returning the precious postcard, Csilla told me to give it to an English friend she had in Chelmsford, Essex, rather than risk the post. I duly contacted the friend and she told me her brother would collect it from me instead, in London. To my amazement, and yet again, Credo, quia absurdum, the brother told me he was a regular club player and he had once won the Chess Informant prize for selecting and placing in the right order the most brilliant games of the half year, as decided by their panel of experts. The chess trail just kept following me around.

* * * *

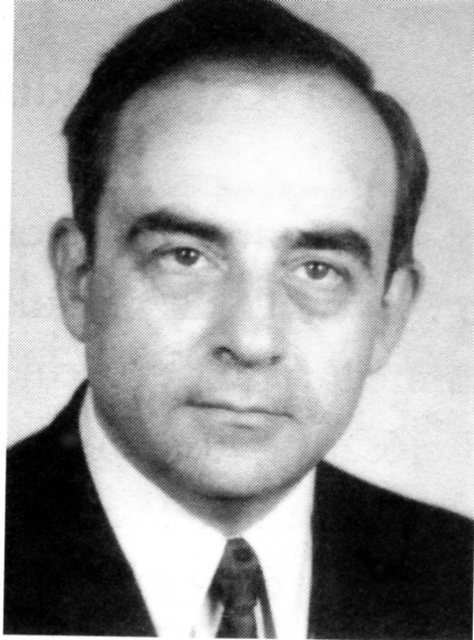

However the ‘first edition’ of the Breyer book was never published because about the same time I received the news that Iván Bottlik was undertaking his own research on Breyer for the third volume in the ‘Hungarian Chess History’ series, as grandmaster Gedeon Barcza, who had worked on the previous volumes, was not in good health and had delegated the work to others.

A page from the ‘first edition’ of the Breyer book – unpublished in 1986!

Over the coming years Iván generously shared his findings with me and little by little, throughout the second half of the 1980s, more and more material was gathered on Breyer. This meant that the pages of the entire book had to be laid out again from scratch, since in those days I used only a typewriter because home computers had not yet reached the marketplace.

But then another problem arose when I took on a very long-term commitment to working three jobs – something like giving a clock simul! So I simply never had the spare time to undertake any ‘labour of love’.

The Hungarian Chess History volume was published in Budapest in 1989, while Iván’s own excellent book, Gyula Breyer: Sein Leben, Werk und Schaffen für die Erneuerung des Schachs [Gyula Breyer: His Life, Work and Creativity for the Renewal of Chess], came out in Germany in 1999.

Iván Bottlik, acclaimed Hungarian chess historian, produced a classic biographical work on Gyula Breyer in German in the 1990s, and generously shared his research with me during the production of The Chess Revolutionary

On the other hand my original manuscript and a considerable amount of extra research material were left lying dormant for a quarter of a century, until a couple of years ago I finally got around to expanding and finishing the project.

Very sadly, not only had Peter Szabó died in the meantime, but also Csilla never got to see the book, as she passed away just a year ago. You can imagine, I felt really bad about taking far too long over the job.

Gyula Breyer’s daughter and grandchildren, Csilla and György Csanádi, attend Breyer’s reinterment in Budapest 1987

In the end, the massive New in Chess tome was twice the size as the unpublished 1980s ‘first edition’, and far more professionally produced, thanks to the efforts of a host of people who I have acknowledged in the book. At 876 pages it certainly fills a big gap in historical chess literature as it will also fill a big gap on any buyer’s bookshelf.

* * * *

We now return to Ed. Winter for his final comment.

A few weeks’ extra effort, at the pre-typesetting stage, could easily have ensured the proper sourcing so obviously needed in a book with such rich historical content.

Ed. Winter has spent so much time talking about sourcing, identifying mistakes, criticising authors, etc., that he has had no time to write anything about the actual chess in Gyula Breyer: The Chess Revolutionary.

So may I reply in kind: ‘A few weeks’ extra effort at the pre-internet-posting stage, reading the 876 pages, could easily have ensured the proper review so obviously needed for a book with such rich historical content.’

But to continue on a positive note, here are a few abridged extracts from reviews of the Breyer book I have seen so far.

* * * *

‘A new book on the ingenious Hungarian Master Gyula Breyer ranks, in my opinion, at the very top of chess publications, along with Kasparov’s various mega series, Nimzowitsch’s My System and Alekhine’s books of his best games. It is distinguished by games, discursive digressions, notes, discreet modern corrections, scholarly research, history, theory and perhaps most impressive of all, Breyer’s Philosophy of the art, science and sport of chess!

. . . This is a chess epic of Tolstoyan magnitude, which will inevitably enter the annals of chess literary classics.’

Grandmaster Raymond Keene

Spectator

* * * * *

‘An epic publication by Jimmy Adams which covers every conceivable aspect of one of the most revolutionary of chess thinkers.

Tragically, Breyer died when on the verge of a breakthrough which could have established him in the same bracket as such grandmasters as Aron Nimzowitsch, Richard Réti, and Savielly Tartakower.’

Grandmaster Raymond Keene

The Times

* * * * *

‘This magnificent tome is the product of decades of research. It presents a great deal of material that was previously both unknown and inaccessible. It is not only essential reading for chess historians, but will also delight anyone with an interest in the development of chess in the early twentieth century, one of the most exciting periods for our game.

. . . With the help of several fellow chess historians and translators, FIDE Master Jimmy Adams has assembled over 200 of Breyer’s games. Most of them are presented with contemporary annotations, sometimes from multiple sources. . . Throughout Adams contributes additions and corrections to these notes in square brackets. This careful method preserves the historical record, while ensuring analytical accuracy. Indeed, many games – especially some complex endgames – are explored in fascinating depth. Just about every game is a hard fight.

. . . A chapter on Breyer’s work as a problem composer, beautifully presented tournament tables, photographs (some of them rare), and indices round off a top-quality book.

In compiling the games and writings of this wonderfully inventive player, Adams has performed a great service to chess history. Most of us tend to buy openings books and works of instruction rather than history. This one is worth making an exception for – and difficult to put down.’

FIDE Master Dr James Vigus

Chess magazine

* * * * *

‘A thoroughly entertaining story that whisks you along to the dramatic end. There is a lot to admire in this clear and readable guide to a largely forgotten chessplayer who was way ahead of his time.

. . . Gyula Breyer’s breakthrough seems to be a highly impressive simultaneous game in 1911 when he destroys Emanuel Lasker in 21 moves, with the game being published at home and abroad. After this the biography reads like an adventure story with each year seeing Breyer have success in tournaments and developing new ideas to put himself ahead of his rivals.

In the past when I have seen books about old players it is difficult to relate to them because they are just names you recognise but can’t put a face to. . . This is largely resolved with the addition of over 70 photos so you can see Akiba Rubinstein, Amos Burn or Efim Bogoljubow, which makes it easier to enjoy.

Breyer’s legacy and influences on the hypermodern school of chess are partly derived from his weekly column in Bécsi Magyar Újság that started in 1921 While I can see how his flurry of opening ideas inspired future generations of players, particularly Réti, I could also easily understand his frustrations with conditions at tournaments. Breyer’s complaints – of poorly-organised events, prize money being embezzled, ever-decreasing prizes and even congresses cancelled just prior to travel – echo familiar tales that do the rounds today.’

International Master Gary Lane

British Chess Magazine

* * * * *

‘. . . 200 interesting games that have many different commentators. These include some of the best players in the world, Lasker, Alekhine, Tarrasch, Rubinstein, Schlechter and Réti, with sometimes two or more annotating the same game, which makes the commentaries almost a debate. The obituary of someone who died young is painful to read because the chess world missed out on the full potential of an amazing individual. Jimmy Adams’ triumph is that he makes you care about Breyer.’

International Master Gary Lane

English Chess Federation Newsletter

* * * * *

‘A magnificent tribute to one of the unsung heroes of the early 20th century. . . This book has almost everything one could want in a game collection. . . It is a book that all those with an interest in chess history will want to have.’

International Master John Donaldson

* * * * *

‘For this book Jimmy Adams has drawn together 240 of Breyer’s games and many of his newspaper and magazine articles, which are translated into English for the very first time. He wrote beautifully – it’s quite amazing that 90 years on, a player’s musings about chess still seem fresh and thought provoking. I particularly enjoyed his article on the mathematical value of pieces (a mistaken conception in Breyer’s view) and a very original way of assigning mathematical values to squares. As for his games, despite his poor health, he was an uncompromising fighter – his play reminds me of Pillsbury’s in that regard – and he produced some stunning games.’

Grandmaster Matthew Sadler

New in Chess Magazine

* * * * *

‘Today the young players’ goal in their chess journey is the rating. After a tournament, many just consult their smart phones incessantly to know if they gained 10-15 points, or if they reached master level (which in the US is 2200). This is their only chess understanding. They don’t see the artistic side, the creative process which makes each chess game unique, and which makes the human spirit something different from all the other animals living on this earth.

The author describes Breyer well on page 8 in the following passage: “But Breyer was not satisfied with merely scoring points and winning prizes, he wanted to explore the vast untapped potential of chess, to expand its horizons, to take it where no one had taken it before – to its outermost limits!”

This book on Breyer is amazing. By today’s standards he is an unknown player who died young. But with many other important names like Alekhine, Nimzowitsch, and Réti, Breyer has contributed to chess by bringing it to the next stage: the “hypermodern revolution”.

. . . When I got this book I thought I was just adding another biography to my shelf of chess biographies. Instead I discovered, thanks to Adams’ meticulous work, a world of chess ideas I had ignored. Breyer was clearly a genius ahead of his time, and his early death did not help the popularization of his ideas.

. . . It is a work of research and a collage. Adams has taken ancient magazines (likely nowadays impossible to find), books, and articles written by or about Breyer, and of course all the annotated games he could find, to create this masterpiece.

The games are annotated by different master players, and Adams has checked the validity of the analysis and provided more when necessary.

. . . I have two other books compiled by Jimmy Adams, one on Chigorin and the other on Zukertort. I love them too!’

Davide Nastasio

Georgia Chess News

* * * * *

‘Top Class. . . Another labour of love from Jimmy Adams and New In Chess. It’s a doorstop of a book over 800 pages, 200+ games and a biography of an influential player. The games have contemporary notes in the main and having them all in the one place, in English, saves you from needing ancient magazines and newspapers. The book is well printed, hardcover and well bound. One of the best chess books of recent times.’

B.W. Thew

Amazon.com

* * * *

A rich selection of material from the book, including my own personal six-page appreciation of Breyer, is presented in PDF format here.

* * * *

I’d like to conclude by dedicating the lyrics of the following number to Mr Edward Winter.

MY WAY

And now the end is near

And so I face the final curtain

My friend, I’ll say it clear

I’ll state my case of which I’m certain

I wrote a book that’s full

I travelled to each and every library

But more, much more than this

I did it my way

Mistakes, I’ve made a few

But then again, too few to mention

I did what I had to do

And saw it through without exemption

I planned each chaptered course

Each careful step along the Breyer way

And more, much more than this

I did it my way

Yes there were times, I’m sure you knew

When I bit off more than I could chew

But through it all, when there was doubt

I ate it up and edited it out

I checked it all and I stood tall

And did it my way

I’ve cheered, I’ve cursed and cried

I’ve had my fill, my share of boozing

And now, as hangovers subside

I find it all so amusing

To think I did all that

And may I say not in a shy way

Oh no, oh no not me

I did it my way

For what is a man, what has he got?

If not himself, then he has naught

To speak his mind and not excuse

The words of one who reviews

The record shows I took the blows

And did it my way

(instrumental)

Yes it was my way. . .

Important note: Any similarity of these lyrics to Paul Anka’s original version should be considered purely coincidental and unintentional . . .