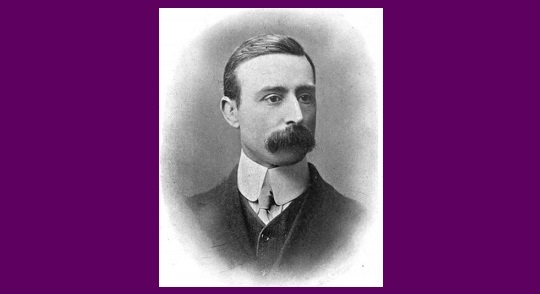

Today marks the 150th birthday of Harold James Ruthven Murray (1868–1955), best known for his A History of Chess, published in 1913.

The fruits of fourteen years of research, this monumental work of scholarship has been described as ‘perhaps the most important chess book in English’ and, less fairly, as ‘inacccessible to the average player’.1

Little was known about Murray’s career, and even less about his life as a chess player, until historian Olimpiu G. Urcan presented a summary of Murray’s chess activity, career and a collection of games on his excellent Patreon webpage.

Murray’s private papers in the Bodleian Library, Oxford reveal that he took up the game around the age of 20, in 1888, while he was at Oxford University studying mathematics.2

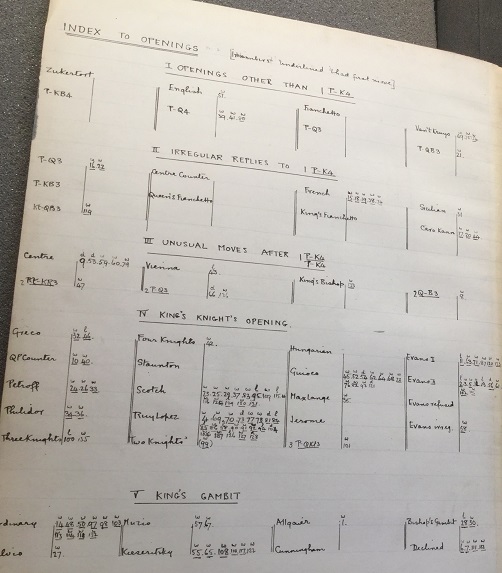

Columns of opening analysis neatly transcribed into his notebook around this time suggest a penchant for gambits.

H.J.R.M. – W. Massey

Ormskirk Chess Club, 1898

1 e4 b6 2 d4 Bb7 3 Bd3 f5 4 exf5 Bxg2 5 Qh5+ g6 6 fxg6

Murray writes in his notebook: ‘In another game, played at Ormskirk Chess Club, 28 March 1898, Black played 6…Nf6 when followed 7 gxh7+ Nxh5 8 Bg6 mate. This, of course is one of Greco’s games.’

7 gxh7+ Kf8 8 hxg8=Q+ Kxg8 9 Qg5 Bxh1 10 h4 Nc6 11d5 Nd4 12 Nd2 e6 13 Qxd8+ Rxd8 14 c3 Bxd5 15 cxd4 Bxd4 16 Ngf3 e5 17 Ne4 Rf8 18 Ke2 c5 19 Bg5 c4 20 Bc2 Bxb2 21 Rg1 1-0

Murray began his career as a teacher, became a headmaster and took up a position as Inspector of Schools in 1901.

While he was spending most of his spare time researching his A History of Chess his itinerant profession enabled him to grow his network of chess contacts:

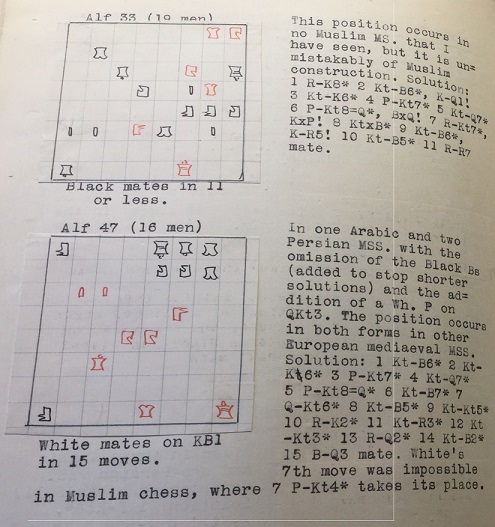

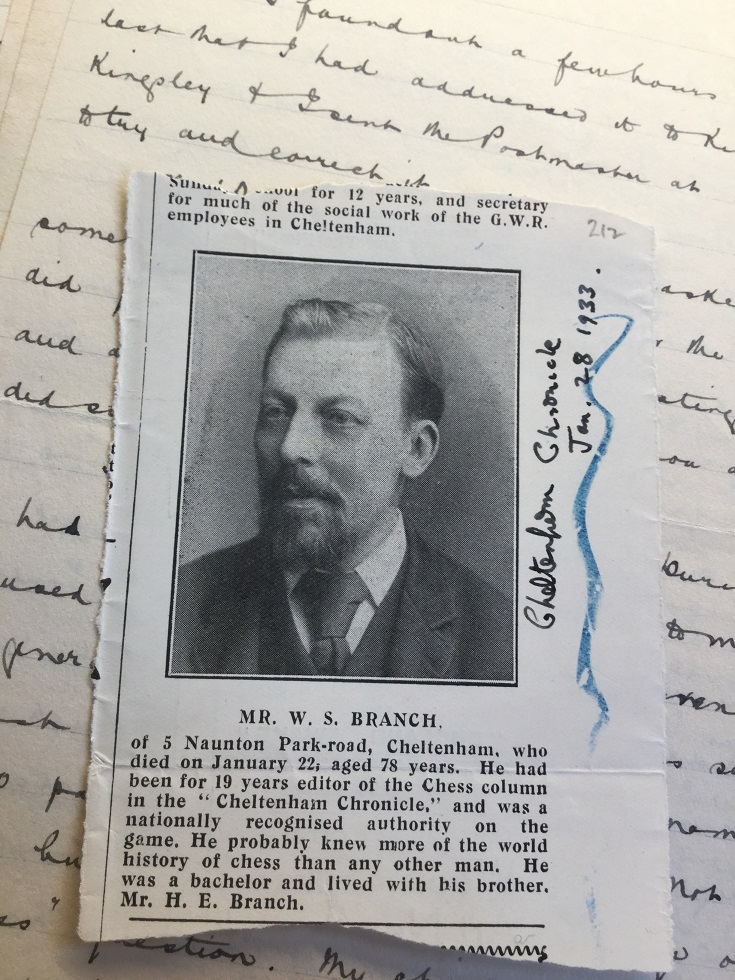

‘I played very little chess between 1902 and 1919. During these years I contributed largely to the British Chess Magazine which I began to take in from 1892. In this way, and in some articles in the Deutsche Wochenschach I became known as a historian of the game. This is not the place to tell the story of the writing of that work which was finally published by the Clarendon Press in 1913, or the friendships to which it gave rise with players and problemists in many parts of the world. During my inspection travels I occasionally visited Chess Clubs, playing C.H. Sherrard at Stourbridge, meeting John Keeble at Norwich, playing Muslim chess with W.S. Branch at Cheltenham.’

A manuscript page from A History of Chess.

Murray writes that ‘an inspection of the Wyggeston School, Leicester, led to some games with H.E. Atkins.’ He recorded only one of them, in which the British Champion misses several decisive moves. In fact, Atkins could not have been kinder if the reputation of his school had rested on a peaceful outcome.

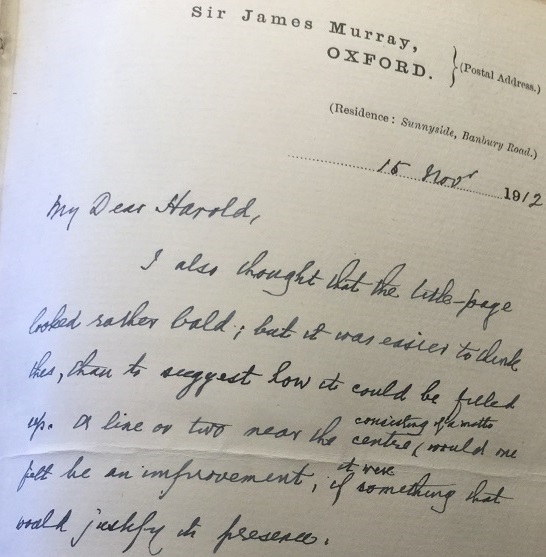

The Murray Papers contain his extensive correspondence with chess chroniclers Keeble and Branch, collector J.G. White, and amateur enthusiasts the world over. They also offer fascinating glimpses of Murray’s relationship with his father, the famous lexicographer James Murray. In one letter James suggests alternative titles for his son’s book, including ‘A History of Chess, in East and West’ and ‘A History of Chess, from the Fourth to the Twentieth Century’.3

Harold politely demurred and stood by the ‘rather bald’ ‘A History of Chess’.

Murray dabbled in poetry too.

BALLADE OF CHESS

When first we played the game of chess

The Giuoco was our play.

To move our Pawns was wickedness,

Let Pieces lead the way,

Advance, attack, defend and slay,

Did we beat you ever? Nay,

You’re master of this game!

In Gambits next we faith confess

The Evans we would play,

The Muzio led through dire distress

To fall your easy prey.

Steinitz and Kieseritzky lay

No better for our fame.

Did we so beat you ever? Nay,

You’re master of this game!

Ambition’s hopes we now repress

And in a sadder day

This aim instead doth us possess –

A draw to bring away;

Though Ruy Lopez be our stay,

The end is still the same,

Lo we so beat you ever? Nay,

You’re master of this game!ENVOY.

Master! You led us on always

You told each opening’s name.

Do we so beat you ever? Nay,

You’re master of this game!

British Chess Magazine, Vol.15 (1895), p.113.

English pastoral:

BELMONT

Builded perdurably

Of grey Cotswold stone

On the slope of the Wolds

Above Gloucester,

A landmark for sailors,

Belmont gathers

Silence from Bradon,

Aloofness from Malvern,

The Forest’s remoteness,

The peace of the Vale,

And from them distils

The quintessence of home;

And of its abundance

Refreshes

The ships as they sail

The Severn’s reaches

From Sharpness to Newham.

In the style of Housman:

DISILLUSIONMENT

Clunton and Clunborough,

Clungerford and Clun,

Searching for stillness,

I’ve tried every one.

Through Clunton thrice daily

A motor doth run

Grinding and hooting

The whole way to Clun.

Through Clungerford echoes

The plonk of the gun,

Clunborough’s stirring,

Avid for fun.

If for quiet you’re seeking,

Clungerford shun –

There’s no peace in Clunborough,

Clunton or Clun.4

Happy birthday, H.J.R.M.

Notes

1. David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess (Oxford University Press, 1992), pp.265-6.

2. MSS. H.J. Murray 72–3, H.J.R. Murray Papers, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

3. MSS. H.J. Murray 158–9, H.J.R. Murray Papers.

4. MSS. H.J. Murray 158–9, H.J.R. Murray Papers.

Sources

Tim Harding, British Chess Literature to 1914: A Handbook for Historians (McFarland, 2018).

H.J.R. Murray, A History of Chess (Oxford University Press, 1913).

H.J.R. Murray Papers, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Matthew Sadler, H.E. Atkins, 9-times British Champion – Part I.

Edward Winter, ‘The Chess Historian H.J.R. Murray’.

With thanks to Richard James.

Jon Manley

→ Commenting on: No Regrets: Boris Spassky at 60

IchessU

→ Commenting on: No Regrets: Boris Spassky at 60

S.B. Cohen

→ Commenting on: Chess and Sex – The Survey

Blair

→ Commenting on: Confessions of a Crooked Chess Master – Part 2