In a recent Perpetual Chess Podcast the chess writer and translator Douglas Griffin pointed out how much fine chess literature is waiting to be translated into English; most of it is in Russian, as you might expect. Griffin has been mining Soviet chess archives for many years and presents some outstanding finds on his excellent blog. A discerning book publisher will surely make his work more widely available before long.

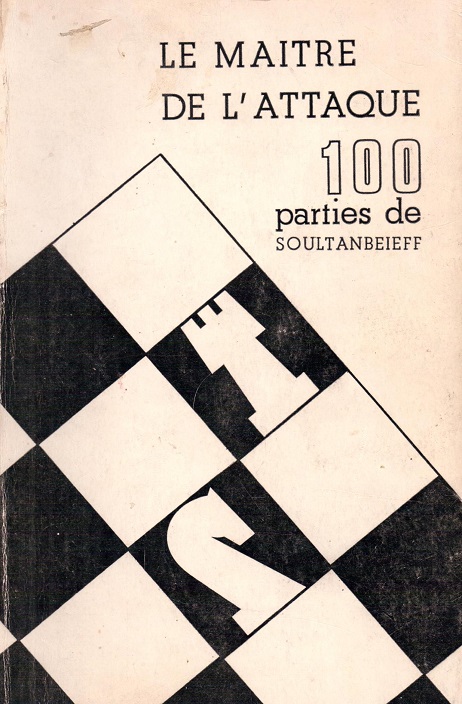

Of the great chess books in other languages seeking a translator, Soultanbéieff’s Le maître de l’attaque (Paris, 1974) will be in the connoisseur’s top ten.

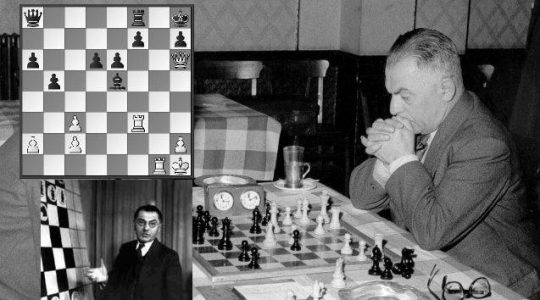

Barely remembered today, Victor Soultanbéieff (1895–1972) was one of the strongest amateur players of the 1930s. Like his contemporary Kurt Richter, ‘the Sultan’ enjoyed a global reputation for swashbuckling play despite relatively few appearances on the international stage.

The pressures of family life and a tough day job hobbled his chess career with fatigue and missed opportunities. Who knows what he might have achieved had circumstances been kinder. See Part 1 and Part 2 for details of his life, combinations and crushing victories over the likes of Tartakower and Nimzowitsch.

Le maître de l’attaque [Master of Attack] is Soultanbéieff’s great legacy. It originally appeared in French in the early 1950s under the title ‘Guide pratique du jeu des combinaisons’ [Practical Guide to Combinations]. In a warm preface, Max Euwe heaps praise on the ‘precise, meticulous, instructive and enjoyable’ book and extols Soultanbéieff’s candour:

‘the author … uses his own games to explain tactical ideas but not only his wins, as is generally the case, but draws and even losses. This gives the book a remarkable objectivity.’

Le maître de l’attaque is an attacking manual packed with spectacular games, fragments, pen-portraits, amusing anecdotes and clear, shrewd advice drawn from the master’s (sometimes bitter) experience.

(The following extract is a translation of Games 14 and 15 of Le maître de l’attaque )

‘Holes’ – the Achilles heel of defence

The hole (French – trou; German – loch) is a square that can no longer be defended by a pawn. Example: white pawns on f2, g3, h2; here the squares f3, g2, f3 create ‘holes’ in White’s position. Another example: black pawns on f6, g7, h6; here the squares f7, g6, h7 create ‘holes’ in Black’s position. In general, holes weaken the position and often allow the opponent’s pieces to infiltrate. The following two games offer pretty conclusive evidence of this.

Pawn March

In chess composition the solver has the advantage of knowing to focus on the challenge in hand (‘mate in two’, ‘White to play and win’, etc.); unlike a real game where the player must assess all of the possibilities in a kaleidoscope of ever-changing positions. To recognise that a given position is ripe for a tactic or a decisive combination, to find and execute that manoeuvre or combination – these are the marks of the master. In the following example Black seizes the opportunity with both hands (20…h4!), but how many times are critical moments like this overlooked and squandered?

The game was played in the Liège Quadrangular Tournament in 1949:

- Soultanbéieff 2/3; 2-3. P. Devos and F. van Seters 1½; Dr Wery 1. It won the beauty prize offered by M-R Anciaux, honorary President of Liège Chess club.

Frits van Seters – Victor Soultanbéieff

Quadrangular Tournament, Liège 1949

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 e3 Be7 6 Nc3 O-O 7 Rc1 c6 8 Bd3 dxc4 9 Bxc4 Nd5 10 Bxe7 Qxe7 11 O-O N5b6

The classical line is 11 Nxc3 12 Rxc3 e5; it has been analysed in the finest detail and requires very precise play from Black. The text move was tried in international tournaments about twenty years ago but without much success. At that time I contributed a special article about it to L’Echiquier magazine (1932).

12 Bb3 e5

13 Re1 (?)

Black’s psychological plan bears fruit: as theory frowns on the variation, my opponent, although a first-class theoretician, did not trouble himself to study it. Instead of this passive move, he should have played, as I showed in the aforementioned article, 13 Ne4! which is stronger than the move commonly played 13 d5 (Nc5!). Confident that 13 Ne4! gives a positional advantage against all Black replies (including Tartakower’s 13…Nf6 14 Nxf6+ gxf6 with weakened kingside), I had adopted this original, bold and yet dubious continuation in a correspondence match with the Lithuanian champion S. Macht (1932-33; drawn: +1, -1, =2). 13 (Ne4) a5!? 14 a3 a4 15 Ba2 Ra5?! 16 Qd2 Rb5?! (a rook manoeuvre à la Sultan Khan) 17 Nc3 e4! 18 Nxb5 exf3 19 Na7 ! Qg5 and after 20 g3 the ‘nail’ on f3 and the ‘holes’ on g2 and h3 caused Black many problems, but the game was drawn on the 51st move.

13…e4! 14 Nd2 Nf6

15 Qc2

Here White intended to play 15 Bc2 and if 15…Bf5 (?) 16 f3 winning a pawn, but noticed that 15…Bg4! 16 f3 exf3 17 gxf3 Bh5 would give Black an advantage.

15…Re8 16 Ne2 Nbd5 17 a3

To parry the threat of Nb4-d3 winning the exchange.

17…Bd7 18 Nf1 b6!

If the a8 rook moves 19 Qc5 would force the exchange of queens owing to the threat of Qxa7, freeing White’s game.

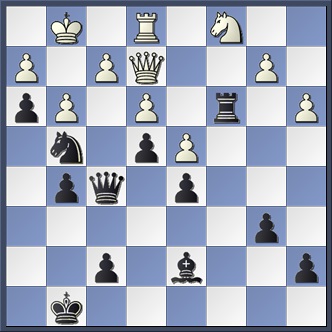

19 Nfg3 Rac8 20 Qb1 h5!

The right plan! White’s play has been a little hesitant (as shown by his knight manoeuvres) and his forces are far from the kingside. So Black seizes the opportunity to launch a quick attack on this side of the board.

21 Bxd5 cxd5 22 Rxc8 Rxc8 23 Nc3

Not wanting to concede to his opponent a clear advantage in the endgame after 23 Rc1 h4 24 Rxc8+ Bxc8 25 Nf1 Ba6, or 23 h3 h4 24 Nf1 Bb5 25 Rc1 Rxc1 26 Qxc1 Qc7 when White is subjected to a mating attack.

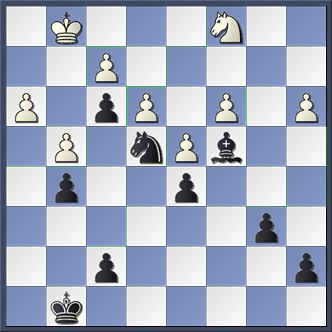

23…h4 24 Nge2 h3! 25 Nf4 Qd6

26 g3

This move was played only after a long think, as White realised the danger the holes on f3 and g2 posed to his king. In any event damage to his king’s position is unavoidable, for example 26 Nxh3 (if 26 gxh3 g5 followed by …Bxh3, …Ng4 etc.) 26…Bxh3 27 gxh3 Qe6 threatening …Nh7, …Rg6+ or …Rh6. after 26 Nxh3 Ng4 the best move is 27 Nf4 g5 28 Nxd5 gxf4 29 Nxf4 with three pawns for the knight while 27 g3 Qh6 28 Kg2 loses to 28…Nxh2.

26…g5 27 Nfe2 Qe6

Already threatening a deadly invasion: Qf4-f3-g2 mate. Weaker was 27…Ng4 when White can put up some resistance with 28 Qd1 Qf6 29 Nf4 gxf4 30 Nxd5 and 31 Nxf4.

28 Qd1 Qf5 29 Nc1 Ng4 30 Qe2 Rxc3!! 0-1

On taking the rook there follows 31…Bb5!! and any queen move allows Black to give mate by Qxf2+ or Qf3-g2. Note that there is no saving White after 29…Ng4.

Defensive tries like 30 Rf1 or Re2 (instead of 30 Qe2) lead to beautiful zugzwang positions:

- 30 Rf1 Rxc3!! (stronger than 30…Bb5 31 Nxb5 Rxc1 32 Qe2 – 32 Nd6 Qxf2+! – Rc2 33 Nd6 and not Qd1 Rd2 or Rxf2) 31 bxc3 Ba4! 32 Qe2 Bb5 33 Qd1 Bc4 34 a4 a5 and White’s large and superior army is completely movebound and quickly mated!

- 30 Re2 Qf3 31 Qf1 Rxc3! 32 bxc3 Bb5 33 Qxh3 (must escape zugzwang!) Bxe2 34 Qg2 Bc4 35 Qxf3 exf3 36 h3 Nf6 37 g4 Ne4 winning because once again White has run out of moves!

A Deadly ‘Nail’

Originally from Poland, as a youth my opponent belonged to the famous Lodz school (Salve, Rubinstein). A fine and deep player, Albert Jarblum is also one of the most likeable I know.

He did not show his best qualities in this game. Leaving theory on his ninth move, he got a passive position and succumbed to an energetic mating attack.

Albert Jarblum – Victor Soultanbéieff

Liège Club Championship, 1923

Four Knights Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 O-O O-O 6 d3 d6 7 Bg5 Bxc3 8 bxc3 Qe7

9 Ne1

Preparing f4 which Black proceeds to prevent. Theory gives 9 Re1 Nd8 10 d4 Ne6 11 Bc1.

9…h6 10 Bh4

It was better to retreat the bishop along the other diagonal.

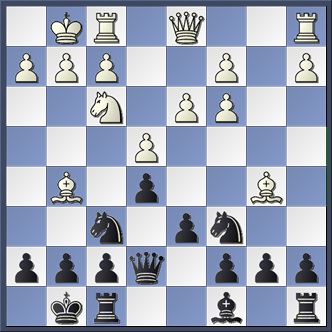

10…g5 11 Bg3 Nd8

The knight heads towards the ‘hole’ on f4.

12 h4

Opening the file on outer flank will favour Black. Znosko-Borovsky recommends instead f3 and d4 to initiate play in the centre, an idea White postpones.

12…Ne6 13 Bc4 Nf4 14 hxg5 hxg5

15 Qd2

This move does not improve the situation. After 15 Bxf4 gxf4 16 g3 Ng4! is very strong.

15…Kg7 16 d4 Rh8 17 f3 Be6 18 Bb3 Rh6 19 Kf2 Rah8 20 Nd3 N6h5 21 Bh2

g4

22 Bxf4

Not 22 g3 Nf6 winning.

22…exf4 23 Bxe6 Qh4+ 24 Kg1

Forced. 24 Ke2 Ng3+ wins.

24…fxe6

25 Nxf4

25 fxg4 would have been a little better whereupon 25…Ng3 (25…Qg3 26 Rf3! offers nothing tangible) 26 Rxf4 Ne2+! 27 Qxe2 Qg3 28 Nf2 Qh2+ 29 Kf1 Qxf4 winning the exchange. If 25 fxg3 Nxg3 26 Rfe1 f3!

25…g3! 26 Nxh3 Nf4! 27 Rfe1 Qg5!

Not only more elegant but also cleaner and quicker than the brutal 27…Nxh3+ 28 gxh3 Qxh3 29 Qg2 Qh4 followed by Qf4 or Qg5 etc. The move played mates or wins the queen.

28 Qe3 Rxh3 29 gxh3 Rxh3! 30 Re2 Qh6 0-1

See also